We weren’t an art museum kind of family, growing up. We were a Velveeta and sitcoms and pop-up camper family. My mother brought three kids to the union with my step-father; he brought three. The main thing the six of us had in common was that we were all stuck orbiting a calamitously ill-advised marriage.

(Also, were there even any art museums in Miami when I was young? I know it’s all chichi and Art Basel-y today, but then?)

We were, however, a board game family. Or, more accurately I suppose, we were board game kids. I discovered art by way of Masterpiece, the old Parker Brothers game. The rules, such as they were, were silly. You tried to outbid the other players at an art auction, but a good percentage of the paintings turned out to be forgeries. I can still remember how this rankled — your fortunes in a game should have something to do with your own wits, they shouldn’t be governed solely by dumb luck.

But it didn’t matter. It wasn’t the game I was interested in; it was the set pieces, the paintings. There were two dozen of them, ranging from Bernardo Martorell’s St. George and the Dragon to Picasso’s Sylvette (Portrait of Mlle. D.), a half-millennium of art reproduced on 3 1/2 x 5 1/2 inch note cards.

I found the paintings by turns puzzling, charming, shocking, mysterious, preachy, fantastic, cryptic, soothing, engrossing. I didn’t love them all. Renoir’s On the Terrace was, even then, too pretty for me, El Greco’s The Assumption of the Virgin, too didactic.

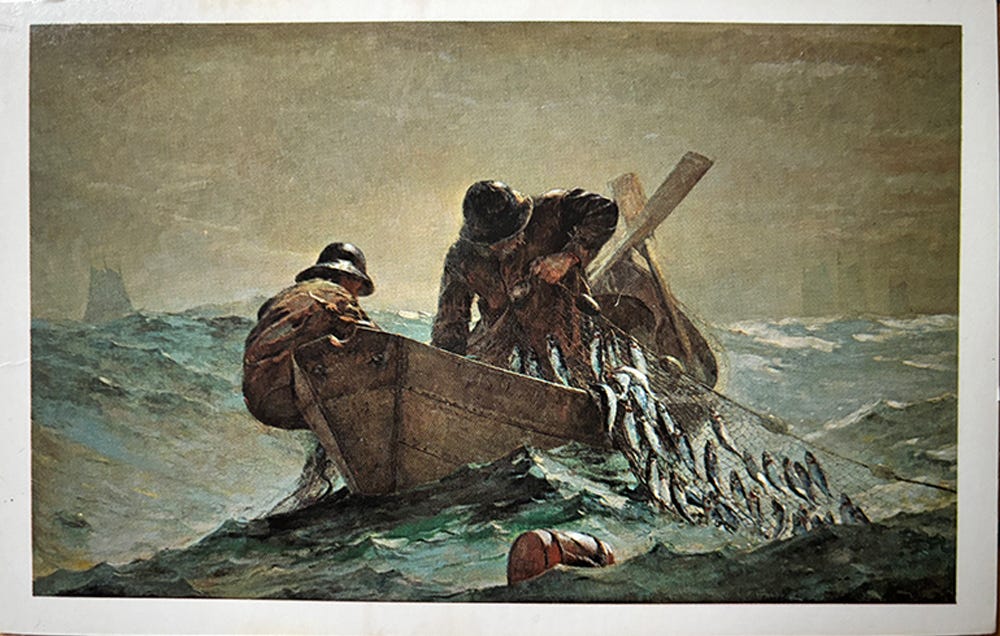

My preteen imagination latched on to the paintings in which the action was frozen mid-scene: Winslow Homer’s The Herring Net, Gustave Caillebotte’s Place de l’Europe on a Rainy Day, and that most narrative of narrative paintings, Hopper’s Nighthawks.

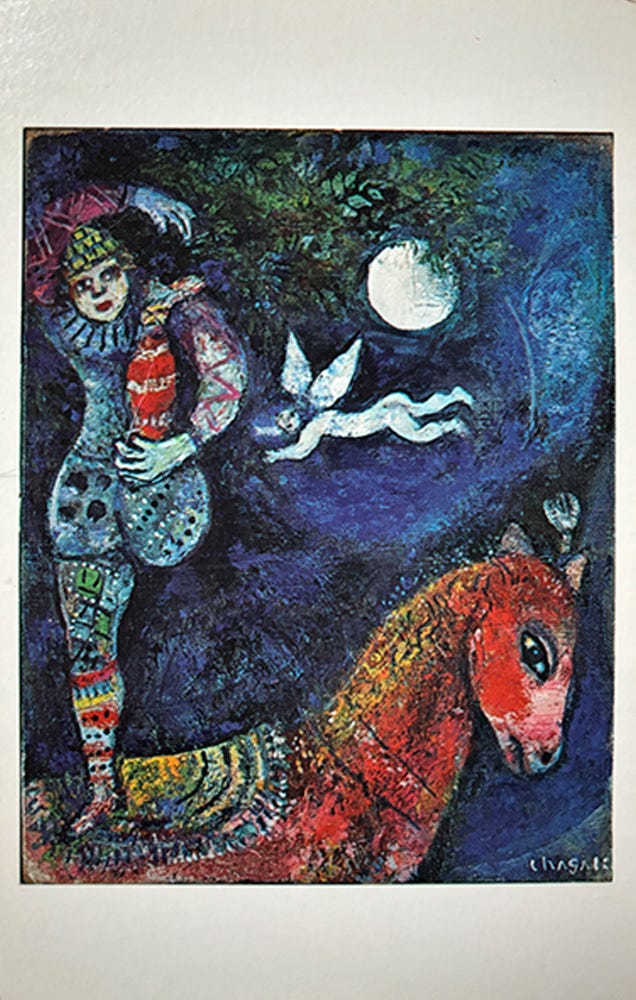

Chagall’s The Circus Rider made me think that the soul has a color, and it’s blue.

I remember feeling all angsty about Jackson Pollock’s Greyed Rainbow. Why was this Art? What was wrong with me that I didn’t get it? It felt like an inside joke of some kind, one that I was meant to be the butt of. While, today, I’m completely and happily reconciled to Pollock, I remain familiar with the angsty feeling — it still overtakes me from time to time in the contemporary wing of my local art museum.

One of the Masterpiece paintings is an obvious forebear to the art I make. But, looking back, I’m unable to remember anything I thought about Hans Hoffman’s The Golden Wall. I guess it didn’t make a big impression on me.

A decade later, I was living and studying in Chicago. I wandered into the Art Institute one day and THERE THEY WERE, my Masterpiece paintings, in the pigmented flesh (the Art Institute affiliation is noted on the backs of the game cards, but I hadn’t retained that information). The first one I spotted (I can’t remember now which one it was), I was like, oh my god that’s from Masterpiece, and then, improbably, I spied another. At some point it dawned on me: they were all there. I got as close to each painting as I could, greedy to drink it in with my own eyes: brushstrokes, edges, how paint was lacquered or dabbled on, oh wow signatures. I stood back to allow the effect of each to wash over me, observe how its color vibrated or whispered, absorb the architecture of its values. The next day I went back and did it all again.

It would sound overly theatrical were I to say that that day at the Art Institute was the second-most formative experience of my painting life (Masterpiece being, of course, the first) so instead I’ll say this: on that day, I was newly on my own, a thousand miles removed from other people’s crap decisions, beginning to become comfortable with thinking what I thought and valuing what I valued. The Masterpiece paintings came to represent that for me — as, in truth, they always had.

This is lovely Weiss. I have missed reading you

Really beautiful writing ♥️